In nature, everything is intertwined and connected. Nature doesn’t know separation or boundaries, one element flows into the other and has a greater impact than man would see with the eyes only. Mutualism, a type of symbiosis, is my favourite example of connection in nature. It describes a close relationship between organisms that is mutually beneficial.

The Chilcotin Ark, of which the South Chilcotin Mountains is a part of, contains 10 biogeoclimatic zones and is a biodiversity hotspot of BC’s interior. 15 of the 29 big game species inhabit this area and their populations are the indicator for functional ecosystems. The most well-known species of the South Chilcotin is the grizzly bear (Ursus arctos). To survive the cold winters in hibernation, grizzlies need food-sources that are high in protein and fats and most of us have seen images of them catching salmon in the rivers. Since the Carpenter Lake dam was built, the river flow has been cut-off and there’s no more salmon available to the bears. Nevertheless, we counted over 250 individuals in our area, sometimes raising as many as four cubs, which is very unusual for grizzlies and is an indicator the bears are eating an extraordinarily nutritious food source. But what can be that rich in protein and fats to feed a grizzly bear sow and her four cubs?

It’s the seeds of Whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis). Whitebark pine is a conifer tree, up to 29 metres in height, mostly common in subalpine terrain of western Canada and western USA. It’s the highest elevation pine tree and often found right at the tree line, on steep slopes. Its shape almost looks like it’s “creeping”.

Whitebark pine seeds weigh an average 180 mg compared to 3 – 13 mg for the seeds of other trees in Whitebark pine forests. (McCaughey et al. 1986). 52% of this weight contains fats, 21% proteins and 21% carbohydrates. This unique combination of nutrients is what makes the seeds a perfect food source for the grizzlies.

But how does the grizzly bear open the pine cones?

They don’t! Here the story leads back to symbiosis. The Clark’s nutcracker (Nucifraga columbiana) has a mutualistic relationship with the Whitebark pine. The seeds are its preferred food source and as he cracks the pine cones open, he disperses the new generation of Whitebark pine by burying them under the ground.

Red squirrels have evolved a similar relationship with the Whitebark pine. They harvest the seeds and bury them in caches under the ground. They are very protective of their food cache, but there’s no chance to protect the nutritious seeds from the sensitive noses and shovel-like claws of grizzlies.

The grizzlies smell the pine seeds in the caches of the Clark’s nutcracker and the squirrels and take their share of this unique food source. All three species benefit from and highly depend on the reproduction of the Whitebark pine.

How can Whitebark pine be so successful in their reproduction, even on dry south slopes?

Again, the answer is symbiosis. Mykhorrizae is a symbiotic relationship between plants and fungi. The fungi that live in the soil disperse in a single-celled layer and one organism can cover an area of several kilometres. The fungi attaches to the root of the Whitebark pine and gathers essential nutrients for the tree, such as nitrogen and phosphorus. In exchange, the tree supplies carbohydrates from its reserves to the fungi.

All these characteristics make Whitebark pine a key species for the South Chilcotin area. But the populations are not as stable as the ecosystem requires. There are two main threats for Whitebark pine: The Mountain Pine Beetle and White Pine Blister Rust.

The Mountain Pine Beetle invades the tree through the bark of the pine to tap into the vascular tissue where the sugar reserves of the tree are stored, slowly sucking it dry, leading to the death of the tree.

White Pine Blister Rust is a fungal disease that was first documented in Vancouver in 1910 with dramatic consequences for the Whitebark pine. Combined with invasions of the Mountain Pine Beetle, the mortality rate of Whitebark pine adds up to 50% of trees in affected areas.

Is there any way we can increase the health of Whitebark pine populations?

When we learned about the importance of Whitebark pine and the threats to local populations, we decided to work with the Whitebark Pine Ecosystem Foundation of Canada. Randy Moody, director of the foundation and passionate plant ecologist, organized research trips into different areas of the South Chilcotins to collect data on the regeneration and growth rate of local Whitebark pine populations.

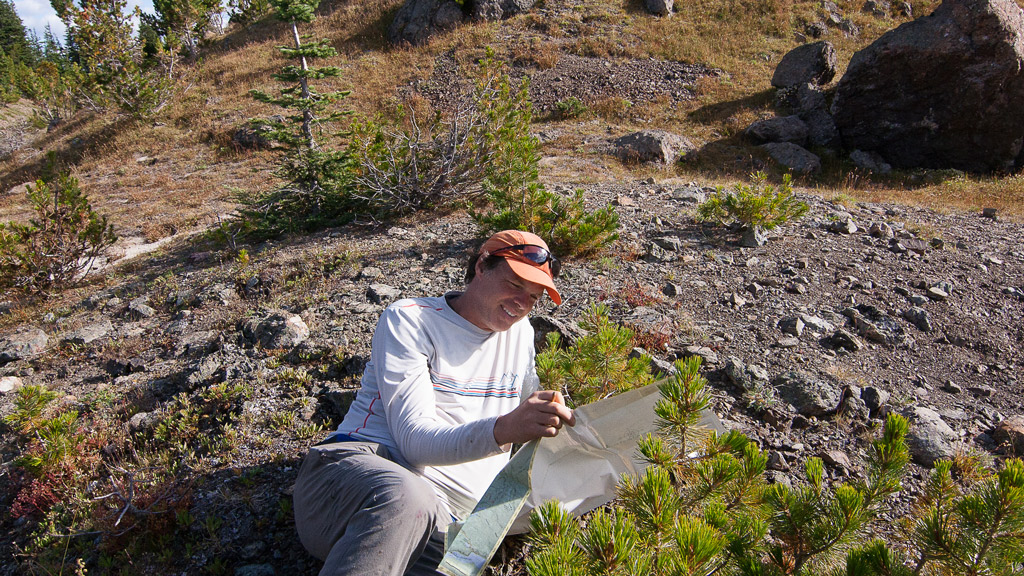

Last year, in September 2019, we hiked to the Eldorado area with three conservation volunteers and Randy to estimate the current health state of local tree populations. Randy introduced us to different coniferous trees and pointed out the key features to identify Whitebark pine. He showed us examples of the White Pine Blister Rust and the Mountain Pine beetle, so that we can estimate the health condition of individual trees. Randy had previously established a transect with high population numbers on different elevation levels. Every 400 metres, we measured the diameter of marked trees, counted numbers of offspring in several height categories and estimated their health condition.

The Whitebark Pine Ecosystem Foundation of Canada and the Wilderness Stewardship Foundation have collected Whitebark pine seeds and replanted them in favourable habitats to increase their chance of establishing a stable population.

The grizzly bear, Clark’s nutcracker, the red squirrel and many more plant and animal species depend on the health of the Whitebark pine in the South Chilcotin Mountains. Hence, it’s critical to monitor their populations and take action to support their reproduction and establishment and so maintain the function of this key species in the South Chilcotin area.

Check out the video about our Whitebark Pine research trip: https://youtu.be/DF9VXyo61r8

Do you feel inspired to take action and participate in hands-on conservation projects?

Visit our website: https://wilderness.stewardship.foudantion to learn more about how you can get involved in our conservation efforts.

Fenja, Germany

February 24th 2020

Links and Resources